Cervical cancer

Highlights

Cervical Cancer Screening

Cervical cancer screening uses two kinds of tests:

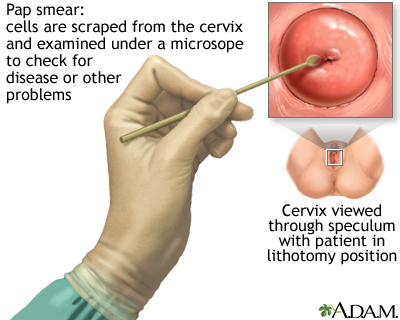

- The Pap test, which checks for abnormal changes in cervical cells that may indicate cancer. The Pap test is the main test used for cervical cancer screening.

- The HPV test, which checks for high-risk strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV) that cause cervical cancer. The HPV test may be used along with a Pap test or after a woman has had an abnormal Pap test result.

In 2012, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) all released revised guidelines that contain similar recommendations for cervical cancer screening. The proposed guidelines recommend:

- Women ages 21 - 29 should be screened once every 3 years with a Pap test.

- Women ages 30 - 65 should be screened with either a Pap test every 3 years OR a Pap test and HPV test every 5 years.

- Women age 65 and older no longer need Pap tests as long as they have had regular Pap tests with normal results. Women who have been diagnosed with pre-cancer should continue to receive regular screenings.

HPV Vaccination

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted disease. High-risk strains of HPV cause cervical cancer, as well as other types of cancer. Low-risk strains of HPV cause genital warts. Nearly all cases of cervical cancer are caused by HPV.

Two vaccines, Gardasil and Cervarix, are available to prevent (not treat) cervical cancer in girls and young women. Gardasil is also approved for boys. Both vaccines protect against HPV-16 and HPV-18, the two HPV strains that cause most cases of cervical cancer. Gardasil, but not Cervarix, also protects against HPV-6 and HPV-11, the two viruses that cause most cases of genital warts.

Current immunization guidelines recommend the HPV vaccine for all girls and boys ages 11 - 12. The vaccine is given as a 3-dose series.

Introduction

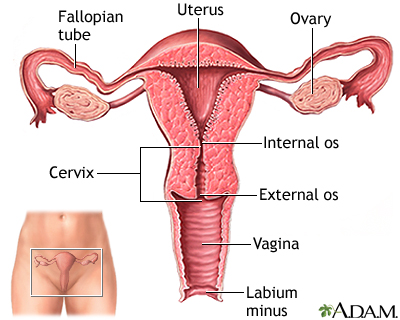

The cervix is the lower third portion of the uterus (womb). It serves as a neck to connect the uterus to the vagina. The opening of the cervix, called the os, remains small and narrow, except during childbirth when it widens to allow a baby to pass from the uterus into the vagina.

Cervical cancer develops in the thin layer of cells called the epithelium, which cover the cervix. Cells found in this tissue have different shapes:

- Squamous cells (flat and scaly). Most cervical cancer arises from changes in the squamous cells of the epithelium (squamous cell carcinoma).

- Columnar cells (column-like). These cells line the cervical glands. Cancers found here are known as adenocarcinomas.

- Mixed carcinomas are cells that combine features of squamous cells and adenocarcinomas.

Cervical cancer usually begins slowly with precancerous abnormalities, and even if cancer develops, it generally progresses very gradually. Cervical cancer usually takes about 10 - 20 years to develop.

Cervical cancer is the most preventable type of cancer and is very treatable in its early stages. Regular Pap tests and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening can help detect this disease early.

Pre-Cancerous Changes in the Cervix

Dysplasia is a term that refers to a pre-cancerous condition. In the case of cervical cancer, dysplasia indicates that some cells on the outside of the cervix (squamous epithelial cells) are abnormal in size and shape and are beginning to grow. However, the abnormal cells are still confined to the surface (epithelial layer). These abnormal cells may eventually become cancerous, but this does not always happen.

Pap test screening can help identify abnormal cells that may be pre-cancerous, but a biopsy is necessary for confirmation. In a biopsy test result, pre-cancerous cells are classified as cervical intraepthilial neoplasia (CIN), which is another term for dysplasia. The severity of CIN is graded on a scale of 1 to 3:

- CIN I is mild dysplasia

- CIN II is moderate dysplasia

- CIN III is severe dysplasia. CIN III is considered the same as carcinoma in situ (CIS) or Stage 0 cervical cancer. The cancer has not yet invaded deeper tissues. However, if not surgically removed, there is a high chance it can progress to invasive cancer.

(For more information on pre-cancer, see the Diagnosis and Screening section of this report.)

Invasive Cervical Cancer

The cells of the epithelium rest on a very thin layer called the basement membrane. Invasive cervical cancer occurs when cancer cells in the epithelium cross this membrane and invade the stroma, the underlying supportive tissue of the cervix.

In later stages, the original cancer may spread to areas surrounding the uterus and cervix or near organs such as the bladder or rectum. It may also spread to distant sites in the body through the bloodstream or the lymph nodes.

Causes

Human Papillomavirus

The human papillomavirus (HPV) is the main cause and risk factor of cervical cancer. Nearly all cases of cervical cancer are caused by HPV. In general, doctors assume that a woman with cervical cancer has been infected with HPV.

HPV is a very common sexually transmitted virus. There are many different types of HPV:

- Low-risk HPV types, such as HPV 6 and 11, cause genital warts but are rarely associated with cancer

- High-risk HPV types cause cervical cancer, as well as cancers of the vagina, vulva, anus, penis, oropharyngeal (throat, tongue, soft palate) and possibly lung.

- HPV 16 and HPV 18 are the causes of most cases of cervical cancer

At least half of sexually active women and men are infected with HPV at some point in their lives. HPV usually goes away on its own. Only 10% of women remain infected for more than 5 years. But sometimes HPV does not go away. A chronic, long-term infection with a high-risk type of HPV can cause changes in cervical cells that eventually lead to cancer.

HPV infection is spread primarily by having sex with a partner infected with HPV. It is transmitted through skin-to-skin contact with infected areas of the genitals, anus, or mouth. Using condoms and limiting the number of sexual partners can help reduce the risk of contracting HPV.

Risk Factors

About 12,000 new cases of invasive cervical cancer are diagnosed each year in the U.S. However, the number of new cervical cancer cases has been declining steadily over the past decades.

Although it is the most preventable type of cancer, each year cervical cancer kills about 4,000 women in the U.S. and about 300,000 women worldwide. In the United States, cervical cancer mortality rates plunged by 74% from 1955 - 1992 thanks to increased screening and early detection with the Pap test.

Age

Cervical cancer is extremely rare in women younger than age 20. The median age of diagnosis is 48 years. Half of all cervical cancer diagnoses occur in women ages 35 - 54 years. About 20% of cervical cancer diagnoses occur in women over 65 years of age, mostly in women who did not receive regular cancer screening during their younger years. .

Race and Poverty

In the United States, Hispanic women are most likely to develop cervical cancer, followed by African-American women. African-American women have the highest death rate from cervical cancer. Asians, Caucasians, and Native American women have the lowest risks for being diagnosed with and dying from cervical cancer.

These differences are probably related to socioeconomic factors. Numerous studies report that high poverty levels are linked with low screening rates. In addition, lack of health insurance, limited transportation, and language difficulties often hinder a poor woman’s access to screening services.

Sexual History

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the main risk factor for cervical cancer. The most important risk factor for HPV is sexual activity with an infected person. Women most at risk for cervical cancer are those with a history of multiple sexual partners, sexual intercourse at age 17 years or younger, or both. A woman who has never been sexually active has a very low risk for developing cervical cancer.

Sexual activity with multiple partners increases the likelihood of many other sexually transmitted infections (chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis). Studies have found an association between chlamydia and cervical cancer risk, including the possibility that chlamydia may prolong HPV infection.

Family History

Women have a higher risk of cervical cancer if they have a first-degree relative (mother, sister) who has had cervical cancer.

Use of Oral Contraceptives

Long-term use of oral contraception (OCs, birth control pills) may increase the risk for cervical cancer. Women who take birth control pills for more than 5 - 10 years appear to have a much higher risk HPV infection (up to four times higher) than those who do not use OCs. (Women taking OCs for fewer than 5 years do not have a significantly higher risk.)

The reasons for this risk from OC use are not entirely clear. Some research suggests that the hormones in OCs might help the virus enter the genetic material of cervical cells. Another possible reason is that women who use OCs may be less likely to use condoms. Latex condoms can help reduce the risk of HPV transmission and other STDs.

Having Many Children

Having given birth to three or more children may increase the risk for cervical cancer.

Smoking

Smoking is associated with a higher risk for pre-cancerous changes (dysplasia) in the cervix and for progression to invasive cervical cancer.

Immunosuppression

Women with weak immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS, are more susceptible to acquiring HPV. Immunocompromised patients are also at higher risk for having cervical pre-cancer develop rapidly into invasive cancer.

Diethylstilbestrol (DES)

From 1938 - 1971, diethylstilbestrol (DES), an estrogen-related drug, was widely prescribed to pregnant women to help prevent miscarriages. The daughters of these women face a higher risk for cervical cancer as well as other gynecological problems. DES is no longer prescribed.

Prevention

The best ways to prevent cervical cancer are:

- Avoid getting infected with human papillomavirus (HPV). Because HPV is sexually transmitted, practicing safe sex and limiting the number of sexual partners can help reduce risk.

- Get vaccinated before becoming sexually active. A vaccine can protect against the major cancer-causing HPV strains in girls and young women who have not yet been exposed to the virus.

- Hve regular Pap test screenings. Pap tests remain the most effective way of catching cervical cancer while it is in its earliest pre-cancerous stages and preventing the development of invasive cervical cancer.

HPV Vaccine

Two vaccines are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to prevent either HPV or cervical cancer: Gardasil and Cervarix.

Gardasil is approved for:

- Girls and women ages 9 - 26, for protection against HPV-16 and HPV-19, the HPV strains that cause most cases of cervical cancer. It also protects against HPV-6 and HPV-11, which cause genital warts.

- Boys and young men ages 9 - 26 years to prevent genital warts.

- Gardasil is also approved to prevent anal cancer in people ages 9 - 26 years.

- Because it protects against four strains of HPV, Gardasil is called a quadrivalent or HPV4 vaccine.

Cervarix is approved for:

- Girls and women ages 10 - 26 for protection against HPV-16 and HPV-19, the HPV strains that cause most cases of cervical cancer.

- Cervarix does not protect against genital warts.

- Cervarix has not been approved for use in boys or men.

- Because it protects against two strains of HPV, Cervarix is called a bivalent or HPV2 vaccine.

Current immunization guidelines recommend:

- Routine vaccination for girls ages 11 - 12 years. The vaccine should be administered in 3 doses, with the second and third doses administered 2 and 6 months after the first dose. The HPV vaccine can be given at the same time as other vaccines. Either Gardasil or Cervarix may be used, and one vaccine can be substituted for another in the 3-dose series.

- Girls as young as age 9 can receive the vaccine at their doctors’ discretion.

- Girls and women ages 13 - 26 who have not been previously immunized or who have not completed the full vaccine series should get vaccinated to catch up on missed doses. [The U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend catch-up doses for ages 13 - 26. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends catch-up for ages 13 - 18. The ACS suggests that women ages 19 - 26 discuss with their doctors the relative risks and benefits of vaccination.]

- Women should not get the vaccine during pregnancy.

- In 2011, the ACIP recommended routine 3-dose vaccination with Gardasil for all 11 - 12 year-old boys. The vaccine is safe for all men through age 26 but is most effective when given at a younger age.

The HPV vaccine can only prevent -- not treat -- HPV infection, genital warts, and cervical cancer. Because the vaccine cannot protect females who are already infected with HPV, doctors recommend that girls and boys get vaccinated before they become sexually active. Studies indicate that the vaccine is nearly 100% effective in preventing cervical cancer and genital warts (caused by the HPV types covered in the vaccine) when given prior to HPV exposure. However, young women who are sexually active may still derive some benefit from the vaccine, at least for protection against any of the four HPV strains that they have not yet acquired.

The most common side effects of the vaccine include discomfort or pain at the injection site, headache, and mild fever.

These vaccines do not protect against all types of cancer-causing HPV. Women should receive regular screening to detect any early signs of cervical cancer. For girls and women who have been sexually active before they receive the vaccine, screening still provides the best protection against cervical cancer.

Condoms

Condoms provide some protection against HPV as well as other sexually transmitted diseases.

Male circumcision may possibly reduce the risk of HPV, but it does not completely prevent it. Men who are circumcised should still use condoms.

Intrauterine Devices (IUDs)

Some evidence suggests that the intrauterine device (IUD) may help protect against cervical cancer. The IUD is a type of birth control that is inserted into the uterus by a health professional. It is a small plastic T-shaped device that contains either the hormone progesterone or copper.

In a large study, women who used an IUD for birth control had half the risk of developing cervical cancer as those who did not use an IUD. The IUD did not decrease HPV infection, but did seem to affect the likelihood that HPV would progress into cervical cancer. Researchers are not certain exactly how the IUD reduces cervical cancer risk, but think that the process of inserting or removing the device may destroy pre-cancerous lesions.

Pap Tests

Regular Pap tests are the most effective way to diagnose cervical cancer when it is still in its earliest, most curable stages. [For more information, see Diagnosis and Screening section of this report.]

Prognosis

A patient’s prognosis for cervical cancer depends on the stage of the cancer, the type of cervical cancer, and the size of the tumor.

General Survival Rates in Women with Cervical Cancer

Over the past 30 years, the death rate from cervical cancer has declined significantly. African-American women tend to have poorer 5-year survival rates than Caucasian women, although survival rates have significantly improved in African-American women in recent years.

The earlier that cervical cancer is detected, the better the odds for survival.

Survival Rates and Cervical Cancer Stage

About half of cervical cancer cases are diagnosed in the early stages when the cancer is confined to the cervix (localized; Stage I). About 35% of cases are diagnosed after the cancer has spread to adjacent areas or lymph nodes (regional; Stage II/III), and about 10% of cases are diagnosed when the cancer has already spread to distant regions (metastasized; Stage IV).

Depending on the stage and spread of cancer, 5-year survival rates are:

- 91% for localized cervical cancer

- 57% for regional cancer

- 16% for metastasized cancer

Symptoms

Most women with dysplasia or pre-invasive cancer have no symptoms. Screening tests, therefore, are very important.

Symptoms of invasive cancer include:

- Unusual vaginal bleeding. Bleeding may stop and start again between regular periods, or there may be bleeding after menopause. Unexpected bleeding can also occur after intercourse or a pelvic exam. Menstrual periods sometimes last longer or are heavier than usual.

- Increased vaginal discharge, which may contain blood. The discharge may occur between periods or after menopause.

- Pelvic pain or pain during sexual intercourse.

These symptoms are not exclusive to cervical cancer. Sexually transmitted diseases, for instance, can cause similar symptoms.

Diagnosis and Screening

The changes that lead to cervical cancer develop slowly. Screening tests performed during regular gynecologic examinations can detect early changes. The two tests used for cervical cancer screening are:

- The Pap test, which can detect pre-cancerous cell changes and cervical cancer. This test is used for all women ages 21- 65.

- The HPV (human papillomavirus) test, which may be used along with a Pap test or after a woman has had an abnormal Pap test result. The HPV test can identify the high-risk types of HPV that are known to cause cervical cancer. This test is not used for women younger than age 30 because HPV is very common in this age group. In younger women, the virus usually goes away on its own within 2 years.

Pap Test

The Papanicolaou test, better known as the Pap test or Pap smear, can help detect cervical cancer when it is in its earliest stages. It can also detect pre-cancerous changes in cells. Use of the Pap test has significantly reduced the death rate from cervical cancer. Most cases of cervical cancer occur in women who have not had regular Pap tests.

Preparing for a Pap Test. To help get the most accurate results, doctors recommend scheduling a Pap test for the 10 - 20 days after menstruation begins. Those are the best days for obtaining the most accurate results. The Pap test should not be performed during menstruation.

In the 24 - 48 hours before the test:

- Do not have sexual intercourse

- Do not use vaginal spermicides, lubricants, or tampons

- Do not douche (in general, douching is not recommended at all)

The Procedure. A Pap test is usually painless, although some women may have some discomfort.

- The test is done in a doctor's office. The woman removes her clothes from the waist down and puts on a medical gown. She lies on her back on the examination table, bends her knees, and puts her feet in supports (called stirrups) at the end of the table.

- The doctor inserts a plastic or metal device (called a speculum) into her vagina to widen it.

- Using a spatula, brush, or both, the doctor gently scrapes the surface of the cervix, and sometimes the upper vagina, to gather living cells. The doctor will also obtain cells from inside the cervical canal. The scraping is completely painless.

- The cells are preserved, stained for microscopic viewing, and then analyzed under a microscope by a specialist known as a cytopathologist.

Reliability and Accuracy. The Pap test is not a perfectly reliable measure of a woman's risk for cervical cancer. In general, about 10% of Pap tests have abnormal results, but only about 0.1% of the women who have these results actually have cancer. In most cases, abnormal cells are low grade and not likely to progress to cancer or are due to benign conditions, including natural cell changes after menopause.

No test is 100% accurate, and it is possible for the Pap test to miss the presence of cancer. However, if abnormal cells are missed on one test, they are likely to be spotted during the next one without a significant danger.

New tests and methods have been developed to improve the accuracy of the Pap test in detecting cancer cells. For example, there are several computerized Pap test systems that are used to rescreen the original smear. These systems are either used to detect abnormal samples that may have been missed by manual review methods or are used in place of a human cytotechnologist. There is not yet enough evidence to know whether or not computerized methods are superior to conventional Pap testing.

Newer, thin-layer liquid based tests (ThinPrep, SurePath) use the original cervical sample, which is rinsed in a special solution to thin the mucus (rather than dried). The fluid is examined for evidence of abnormal cells as well as HPV and other early abnormalities. Some studies have found liquid-based Pap tests to be more accurate than the standard Pap test.

Current Cervical Cancer Screening Recommendations

General guidelines for cervical cancer screening recommend:

- Initial Screening. Women should begin to have Pap tests at age 21 regardless of whether or not they have been sexually active. Women under age 21 should not be screened.

- Women Ages 21 - 29. Women ages 21 - 29 who are at average risk for cervical cancer should be screened once every 3 years with a Pap test. They do not need a HPV test unless they have had an abnormal Pap test result.

- Women Ages 30 - 65. Women in this age bracket can have either a Pap test every 3 years OR a Pap test and HPV test every 5 years.

- Women Ages 65 and Older. Women age 65 and older no longer need Pap tests as long as they have had regular Pap tests with normal results. Women who have been diagnosed with pre-cancer should continue to receive regular screenings.

- After a Hysterectomy. Women who have had a hysterectomy that preserves the cervix (called a supracervical hysterectomy) should continue to have Pap screening according to the guidelines listed above.

How Pap Test Results Are Reported

The cells viewed in a cervical smear sample are classified on a scale representing the spectrum of cell changes from normal to cancerous. The Pap test is first characterized as either normal or abnormal.

Once abnormal epithelial cells are identified, the doctor must decide whether the patient needs a repeat Pap test, an HPV test, or more invasive testing with colposcopy and biopsy. (Colposcopy is a procedure used to magnify the cervix and to help find lesions for biopsy). To help the doctor make the decision, the abnormal cells are divided into categories, depending on the degree of abnormality, and whether they are squamous or glandular (adenocarcinoma).

Squamous cell carcinoma represents the large majority of all cervical cancers. The remaining cases are either a combination of squamous and glandular, or rarer types.

The Bethesda System (TBS) is used to report Pap test results. It classifies abnormal results as atypical squamous cells (ASC with subtypes of ASC-US and ASC-H), squamous intraepithelial lesions (SILs) or atypical glandular cells.

Atypical Squamous Cells. Atypical squamous cells (ASC) are mildly abnormal cells on the surface of the cervix. It is difficult to know if they are pre-cancerous. They may be normal cells with changes simply be caused by inflammation. Atypical squamous cells are further categorized as ASC-US or ASC-H:

- ASC-US. Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) are the lowest risk abnormal cells and are very often not pre-cancerous. Women with ASC-US need to have a repeat PAP test in 6 - 12 months and the doctor may also recommend a HPV test and possibly colposcopy.

- ASC-H. This category refers to atypical squamous cells that may indicate high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL). Such women have a higher risk of having CIN II and III. All are referred for colposcopy.

Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions (SILs). Squamous intraepithelial lesions (SILs) are classified as either low-grade (LGSIL) or high-grade (HGSIL). High-grade SILs are more serious than low-grade SILs, and need to be treated because they can develop into invasive cancer. Pap tests can identify the presence of SILs but not their grade. All patients with SILs should undergo colposcopy. A colposcopy can determine whether SILs are high-grade or low-grade and whether treatment is required.

Atypical Glandular Cells and Adenocarcinoma. Atypical glandular cells pose a higher risk for cancerous changes than atypical squamous cells or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Patients with atypical glandular cells need colposcopy and endocervical testing. Adenocarcinoma refers to glandular cells that are cancerous.

Colposcopy and Biopsy

The Pap test shows only the presence of abnormal cells. It is useful simply as a screening test that identifies women who may have pre-invasive or early cancerous changes. For a definitive diagnosis, the next step is usually colposcopy, during which the cervix is visualized under low power magnification. The surgeon takes samples of suspicious cells for biopsies. A biopsy will determine the stage of the pre-cancerous growth or whether invasive cancer is present.

The Procedure. Colposcopy can be performed in a doctor's office without anesthesia in 10 - 15 minutes. It causes about as much discomfort as mild menstrual cramps:

- First, using a speculum to keep the vagina open, the doctor aims a light at the cervix.

- The doctor then looks through the eyepiece of a special microscope, known as a colposcope, to view the cervix.

- A biopsy (a sampling of the tissue) is taken of suspicious areas, of the endocervical canal (the inner part of the cervix and uterus), and any abnormal-looking areas. This may cause cramping or pinching.

After the colposcopy, the woman may have a brownish discharge from an iron solution called Monsel's solution, which the doctor applies to prevent bleeding. Doctors usually advise sexual abstinence for 1 - 2 weeks.

Biopsy Results

The pre-cancerous changes from biopsy results of colposcopy are called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. They are graded according to severity: CIN I, CIN II, and CIN III.

- CIN I is classified as mild dysplasia. It is equivalent to a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LGSIL) identified by a Pap test. CIN I may progress if untreated but often goes away without treatment.

- CIN II is classified as moderate dysplasia. It is equivalent to a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL) found in a Pap test.

- CIN III is classified as severe dysplasia. It is the most aggressive form of dysplasia. It is also equivalent to a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

CIN III is considered the same as carcinoma in situ (CIS) or Stage 0 cervical cancer. In both CIN III and CIS the pre-cancerous cells still rest on the surface of the cervix and have not yet invaded deeper tissues. However, if not surgically removed, there is a high chance that CIN III or CIS can progress to invasive cancer.

Follow-Up Procedures. Women with evidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or cervical cancer need treatment. Women with biopsies that show low-grade abnormal cells, but whose cervix is otherwise normal, are generally given follow-up colposcopies.

If a biopsy detects invasive cancer, the patient will need additional tests to find out how far the cancer has spread. Tests to stage cancer may include a computed tomography (CT) scan (to check for the spread of the disease to lymph nodes and areas around the pelvic region), chest x-ray, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET) scan, and other imaging tests.

Treatment

Treatment of Pre-Invasive Cancer

Treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), including pre-invasive cancer, depends on the type and extent of abnormal changes. Some of the treatments for CIN are also used for early-stage cancer.

- CIN I often goes away on its own. Careful follow up is required to make certain that the Pap smear and colposcopic exam return to normal.

- CIN II or CIN III may turn into invasive cancer if the suspicious area is not removed. This is often done using an outpatient technique called loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). [See Surgery section.]

- If doctors cannot see extensive areas of CIN II or III with colposcopy or if these areas have spread into the mucous membrane in the cervical canal, a more aggressive procedure called conization (cone biopsy) may be required. [See Surgery section.] Since CIN III is considered equivalent to Stage 0 cervical cancer, other procedures may be used if LEEP or conization are inadequate.

Treatment of Invasive Cervical Cancer

In contrast to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, cervical cancer represents true invasion of cells beyond the epithelium into surrounding tissue. Cervical cancer may be detected in a biopsy performed during colposcopy for an abnormal Pap smear, or it may be visible to the naked eye when the doctor performs a speculum exam.

After making a diagnosis, the doctor will classify the stage of the cancer according to how far the disease has spread into the lining of the cervix, throughout the cervix, or beyond. Doctors use these classifications to determine treatment and prognosis.

Stages of Cervical Cancer

Stage 0. Stage 0 cancer is also called carcinoma in situ. It is equivalent to CIN III pre-invasive cancer. In stage 0, the cancer cells are confined to the first layer of cervical tissue (the epithelium) lining the cervix and have not yet spread further in the cervix.

Stage I. Stage I is invasive cancer, but the tumor is confined to the cervix. This stage is further categorized as IA and IB, which each have further subcategorizations based on the size of the tumor:

- In stage IA, the cancer cells can be seen only under a microscope. In stage IA1, there is minimal invasion (less than 3 mm and less than 7 mm wide) In stage IA2, there is deeper invasion of 3 - 5 mm) but the microscopic tumor is still less than 7 mm wide.

- In stage IB, the cancer is either visible without a microscope, or it is still microscopic but is more than 5 mm deep or 7 mm wide. Cancer that can be seen without a microscope is divided into Stage IB1 and Stage IB2. In stage IB1, the cancer is smaller than 4 cm. In stage IB2, the cancer is larger than 4 cm.

Stage II. Stage II invasive cancer has spread beyond the cervix, but it has not spread to the pelvic side wall. This stage is further categorized as IIA and IIB.

- In stage IIA, the cancer has spread to the upper two-thirds of the vagina but not to the uterus.

- In stage IIB, the cancer has spread beyond the vagina into the tissues of the uterus.

Stage III. In stage III, the cancer has spread to the lower third of the vagina.

- In stage IIIA, the cancer has not spread to the pelvic wall.

- In stage IIIB, the cancer has spread to the pelvic wall. The tumor may have become large enough to block the ureters of the kidney, which can cause the kidney to stop functioning.

Stage IV. Stage IV is advanced (metastasized) cancer. The cancer has spread to other organs or parts of the body.

- In stage IVA, the cancer has spread to organs located near the cervix, such as the bladder or rectum.

- In stage IVB, the cancer has spread beyond the pelvic area to other parts of the body, such as the liver, intestinal tract, or lungs.

Treatment Options by Stage

Treatments for cervical cancer depend on the stage of the cancer. Clinical trials investigating new treatment approaches are available for all stages of cervical cancer.

Stage 0. Stage 0 cancer is carcinoma in situ (CIN III) and is considered a pre-invasive cancer. Treatment options include:

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP)

- Laser surgery

- Conization

- Cryosurgery

- Total (simple) hysterectomy (removal of uterus and cervix), for women who no longer want children

- Internal radiation therapy, for women who cannot have surgery

Stage IA1. Treatment options for stage IA1 may include:

- Conization

- Total hysterectomy

- Radical hysterectomy (removal of uterus, cervix, part of vagina, and pelvic lymph nodes)

- Internal radiation therapy

Stage IA2. Treatment options for stage IA2 may include:

- Radical hysterectomy

- External beam radiation therapy plus brachytherapy (implantation of radioactive pellets)

- Radical trachelectomy (removal of the cervix but not the uterus) may be an option for some women who want to preserve fertility

Stage IB1. Treatment options for stage IB1 may include:

- Radical hysterectomy

- High-dose internal and external radiation therapy

- Radical trachelectomy

Stage IB2. Treatment options for stage IB2 may include:

- Combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy

- Radical hysterectomy, followed by radiation therapy (and possibly chemotherapy) if cancer cells are found.

Stage IIA. Treatment options for stage IIA may include:

- Internal and external radiation therapy

- Radiation therapy plus chemotherapy

- Radical hysterectomy followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy

Stage IIB. Treatment options for stage IIB may include:

- Combined internal and external radiation therapy along with chemotherapy with cisplatin

- Other drugs may be given along with cisplatin

Stage III. Treatment options for stage IIIA and stage IIIB may include combined internal and external radiation therapy plus chemotherapy Stage IVA.

Treatment options for stage IVA may include combined internal and external radiation therapy plus chemotherapy.

Stage IVB. Stage IVB cancer is generally not considered curable. Treatment options may include:

- Radiation therapy to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life

- Chemotherapy with cisplatin or carboplatin in combination with another drug (paclitaxel, gemcitabine, topotecan, or vinorelbine)

Recurrent Cancer. Cervical cancer may recur locally in the lymph nodes near the cervix, it may spread to distant sites, such as the lung or bones, or it may appear both locally and in distant locations. Treatment options depend on where the cancer has recurred. They include:

- Pelvic exenteration if cancer has spread to only local areas. This involves surgical removal of the cervix, uterus, vagina, and perhaps the bladder, lower colon, or rectum.

- Chemotherapy or radiation if cancer has spread to distant area.

Treatment of Pregnant Women with Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is one of the most common cancers diagnosed during pregnancy. To diagnose the condition, a cervical biopsy, in which a small amount of tissue is removed for diagnosis, can be performed anytime during the pregnancy. However, a cone biopsy (conization), which removes larger amounts of tissue, is typically delayed until after the first trimester to reduce the risk of causing a miscarriage. Conization does increase the risk for preterm delivery and may increase this risk for future pregnancies. The loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP/LLETZ) may be performed in centers equipped to handle it, but should be reserved only for patients in whom invasive disease is strongly suspected.

Treatment of cervical cancer depends in part on whether a patient wishes to continue the pregnancy, and her desire for future fertility. For pregnant women who want to continue the pregnancy, and preserve fertility when possible, treatment options may include:

- If the abnormality is diagnosed as dysplasia or pre-invasive cancer, treatment is usually delayed until after the mother gives birth. The baby is delivered vaginally. It is rare for cervical cancer to progress from pre-invasive to invasive within the space of 1 - 2 trimesters.

- For stage IA1, a cesarean section is performed at term, or earlier if the fetus is viable. After delivery, LEEP/LLETZ or conization is performed.

- For stages IA2 and IB1, a cesarean section and radical hysterectomy is performed when the fetus is viable. After delivery, radiation and chemotherapy is given.

- For stages IB2 - IVA, a cesarean section is performed as soon as possible. Treatment should not be delayed beyond weeks 32 - 34. For patients who have a delayed cesarean, chemotherapy may be given. After delivery, the patient is treated with radiation and chemotherapy.

- For stage IVB, a pregnancy of less than 20 weeks is terminated, and the patient is treated with chemotherapy. For pregnancies more than 20 weeks, a cesarean may be delayed while the woman receives chemotherapy.

Surgery

In the early stages of cervical cancer, surgery is usually the preferred primary treatment approach. Not all women are candidates for all surgical procedures.

Surgery procedures by stage are:

- Loop Electrosurgical Excision Procedure (LEEP) and Laser Surgery. Used for pre-invasive cancer including cervical intrapethelial neoplasia (CIN) and stage 0.

- Conization. Used for treating pre-invasive cancer (CIN and stage 0) and invasive cancer stage IA1.

- Cryosurgery. Used for stage 0.

- Total (Simple) Hysterectomy. Used for stage 0, stage IA1.

- Radical Hysterectomy. Used for stage IA2, stage IB1 and IB2, stage IIA.

- Radical Trachelectomy. Used for select women with stage IA2, stage IB1.

Loop Electrosurgical Excision Procedure

Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), also called large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ), uses a high frequency electrical current to cut away diseased tissue.

- A local anesthetic is applied to the cervix, and a wire loop is inserted into the vagina.

- A button-sized slice of tissue is removed from the cervix for examination.

- A deeper slice is used to evaluate the endocervical canal.

The procedure is done in one office visit. Extensive and deep sections of damaged tissue can be effectively removed in this visit. Disease can be cured in one treatment. When used for dysplasia, it appears to be as effective as more invasive procedures.

Laser Surgery

Laser surgery for cervical cancer uses a laser beam, in place of a knife, to burn off abnormal cells or to remove pieces tissue for biopsy. The laser beam is directed through the vagina.

Conization

Conization is a surgical procedure that removes a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix. Conization uses either a heated wire, like LEEP, or it may involve a scalpel or laser (in which case the procedure is sometimes called “cone knife cone biopsy”). The surgery is performed under general anesthesia in an operating room. With conization, the ability to become pregnant can be preserved in most cases.

Hysterectomy

A hysterectomy attempts to eliminate the cancerous tissue by removing the uterus. In women of childbearing age, the ovaries can usually be left intact. Although a woman who has a hysterectomy but retains her ovaries cannot bear children, she will not go into premature menopause.

Women with cervical cancer usually have either a total (simple) hysterectomy or a radical hysterectomy.

Total Hysterectomy. A total (also called simple) hysterectomy involves the removal of the uterus and the cervix, but leaves the parametrium (tissue surrounding the uterus) and vagina intact. Lymph nodes in the pelvis are not usually removed. The uterus may be removed through an open abdominal incision or vaginally. There are various ways to perform vaginal hysterectomy, including laparoscopically. A simple hysterectomy is usually performed to treat stage IA1 cervical cancer. [For more information on hysterectomy procedures, see In-Depth Report #73: Uterine fibroids and hysterectomy.]

Radical Hysterectomy. A radical hysterectomy removes not only the uterus and the cervix but also the parametrium, the supporting ligaments, the upper vagina, and some or all of the pelvic lymph nodes (a procedure called lymphadenectomy). The fallopian tubes and ovaries are not usually removed, (a procedure called bilateral-salpingo-oopherectomy) unless there are other medical reasons for doing so. Radical hysterectomy is used to treat cervical cancers in stages IA2, IB1, and IB2.

Pelvic Exenteration. If the cancerous tumor recurs within the pelvis after primary treatment, the patient may need a more extreme procedure called a pelvic exenteration, which combines radical hysterectomy with removal of the bladder and rectum. (In such cases, plastic surgery may be needed afterward to recreate an artificial vagina.)

Recovery. Hospital stays for simple hysterectomy range from 1 - 2 days for vaginal hysterectomy to 3 - 5 days for abdominal hysterectomy. Total recovery time is generally 2 - 3 weeks for vaginal hysterectomy and 4 - 6 weeks for abdominal hysterectomy. Radical hysterectomy generally requires a 5 - 7 hospital stay and about a 6-week recovery period.

Side Effects. Side effects include difficulty emptying the bladder or bowels and a painful lower abdomen (if an abdominal incision was used). Normal activity, including intercourse, can be resumed in about 4 - 8 weeks. The effects of hysterectomy on sexuality vary among women. Some women note a change in their orgasmic response because they no longer experience uterine contractions.

Once the uterus is removed, menstruation will cease. If the ovaries are removed, the symptoms of menopause will begin. These symptoms are likely to be more severe in surgical menopause than in natural menopause. The patient should discuss the benefits and risks of hormone replacement therapy with her doctor.

[For more information on hysterectomy, see In-Depth Report #73: Uterine fibroids and hysterectomy.]

Radical Trachelectomy

For some women with stage IA2 and stage IB1 cancer, radical trachelectomy may be a fertility-sparing alternative to hysterectomy. Radical trachelectomy involves removing the cervix, surrounding lymph nodes, and upper part of the vagina. The uterus is then reattached to the remaining vagina. Patients must meet strict criteria in terms of lesion size and lymph node involvement.

Radical trachelectomy poses a high risk for miscarriage during future pregnancy, but about half of women who have had this procedure have been able to carry a baby to term. The baby is delivered by cesarean section.

Radiation

Radiation therapy is a treatment option for early stage cervical cancer (stages IA2 - IB1). Radiation given along with cisplatin-based chemotherapy is commonly used for stages IB2 - IVA cervical cancer.

There are two types of radiation therapy:

- External beam radiation uses high-energy x-rays aimed at the pelvic area from an outside machine. It usually involves a short period of direct-radiation 5 days a week for about 6 weeks in an outpatient setting.

- Internal radiation (also called brachytherapy or intracavitary radiation) is designed to deliver high doses of radiation to the local tumor area. Radioactive material encased in capsules is inserted into the uterus and placed against the cervix as close to the cancerous cells as possible. Radiation implants may also be inserted directly into the tumor using a needle. Low-dose brachytherapy usually requires a hospital stay for a few days, as the patient must remain immobilized. High-dose brachytherapy is given on an outpatient basis during several short treatments.

Both types of radiation therapy may be used together.

In order to be effective, radiation therapy must be powerful enough to destroy the cancer cells' capacity to grow and divide. This means that normal cells are also affected, which may cause significant side effects. Fortunately, healthy cells usually recover quickly from the damage, whereas abnormal cells do not.

Side Effects. Side effects of radiation therapy include fatigue, redness or dryness in the treated area, diarrhea, frequent or uncomfortable urination, and vaginal dryness, itching, or burning. After treatment, side effects usually disappear.

Long-Term Complications. Complications include proctitis (inflammation of the rectum) and cystitis (inflammation of the bladder). Radiation therapy may also cause vaginal scarring, sexual difficulties, and premature menopause in younger women.

Radiation itself may increase the risk for later development of cancer in the area surrounding the treated tissue. Although newer more precise radiotherapy approaches should reduce this risk, the development of secondary cancers may be of particular concern for younger patients.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses cell-killing drugs called cytotoxic drugs to destroy widespread cancer cells that have spread from the primary tumor and can no longer be treated with surgery or radiation alone. Chemotherapy is usually used along with radiation (a combination called “chemoradiation”) for treatment of stages IB1 - IVB cervical cancer. Chemotherapy can help increase the effectiveness of radiation therapy. In the most advanced cancer stage, IVB, chemotherapy is used palliatively to help relieve symptoms.

Platinum-Based Drugs. Platinum-based drugs are the main chemotherapy treatment for cervical cancer. Cisplatin is the primary drug used. Carboplatin is an alternative platinum drug that is used for treating more advanced cervical cancer.

Other drugs. Other drugs may be given alone or in combination with a platinum-based drug. They include paclitaxel, topotecan, gemcitabine, 5-FU, vinorelbine, and others.

Administration. Chemotherapy is given intravenously at a medical center or doctor's office. The drugs are given in cycles with a period of rest following a period of treatment, to allow recovery from the side effects.

Side Effects. Chemotherapy affects all fast-growing cells, including healthy ones. So, side effects are inevitable. Side effects occur with all chemotherapeutic drugs. They are more severe with higher doses and increase over the course of treatment. Side effects also tend to be more severe when chemotherapy is given along with radiation.

Common side effects may include:

- Nausea and vomiting (drugs can help relieve these side effects)

- Diarrhea

- Temporary hair loss

- Loss of appetite and weight

- Fatigue

Complications. Serious short- and long-term complications can also occur and may vary, depending on the specific drugs used. They include:

- Severe drop in white blood cell count (neutropenia). The reduction in white blood cells suppresses the immune system and makes patients more susceptible to infections.

- Reduction of blood platelets (thrombocytopenia), which can lead to bruising

- Anemia, reduction in red blood cells, is a common side effect of chemotherapy. Chemotherapy-induced anemia is usually treated with erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs, which include epoietin alfa (Epogen, Procrit) and darberpetin alfa (Aranesp). These drugs may contribute to rapid tumor growth in patients with cervical cancer. Doctors need to follow strict dosing guidelines when administering these drugs. Patients should discuss the risks and benefits of erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs with their oncologists. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #57: Anemia ]

- Premature menopause

- Liver and kidney damage

- Problems with concentration, motor function, and memory

Resources

- www.cancer.gov -- National Cancer Institute

- www.cancer.org -- American Cancer Society

- www.acog.org -- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- www.ashastd.org -- American Social Health Association

- www.nccc-online.org -- National Cervical Cancer Coalition

- www.foundationforwomenscancer.org -- Foundation for Women's Cancer

- www.cancer.net -- Cancer.Net

References

Albrechtsen S, Rasmussen S, Thoresen S, Irgens LM, Iversen OE. Pregnancy outcome in women before and after cervical conisation: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2008 Sep 18;337:a1343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1343.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 99: management of abnormal cervical cytology and histology. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Dec;112(6):1419-44.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 109: Cervical Cytology Screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Dec;114(6):1409-1420.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening for cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Nov;120(5):1222-38.

Castellsagué X, Díaz M, Vaccarella S, de Sanjosé S, Muñoz N, Herrero R, et al. Intrauterine device use, cervical infection with human papillomavirus, and risk of cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of 26 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Oct;12(11):1023-31. Epub 2011 Sep 12.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 May 28;59(20):626-9.

Committee on Adolescent Health Care. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 436: evaluation and management of abnormal cervical cytology and histology in adolescents. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Jun;113(6):1422-5.

Committee on Infectious Diseases; American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy statement--recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedules--United States, 2011. Pediatrics. 2011 Feb;127(2):387-8.

Hunter MI, Monk BJ and Tewari KS. Cervical neoplasia in pregnancy. Part 1: screening and management of preinvasive disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(1):3-9.

Hunter MI, Tewari K and Monk BJ. Cervical neoplasia in pregnancy. Part 2: current treatment of invasive disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(1):10-8.

Kahn JA. HPV vaccination for the prevention of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jul 16;361(3):271-8.

Lowy DR, Solomon D, Hildesheim A, Schiller JT, Schiffman M. Human papillomavirus infection and the primary and secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Cancer. 2008 Oct 1;113(7 Suppl):1980-93.

Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, Walter SD, Hanley J, Ferenczy A, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(16): 1579-88.

Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain J, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 May-Jun;62(3):147-72. Epub 2012 Mar 14.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jun 19;156(12):880-91, W312.

Vesco KK, Whitlock EP, Eder M, Burda BU, Senger CA, Lutz K. Risk factors and other epidemiologic considerations for cervical cancer screening: a narrative review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Oct 17. [Epub ahead of print]

Whitlock EP, Vesco KK, Eder M, Lin JS, Senger CA, Burda BU. Liquid-based cytology and human papillomavirus testing to screen for cervical cancer: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Oct 17. [Epub ahead of print]

Wright TC Jr., Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ and Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(4): 346-55.

Wright TC Jr., Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ and Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(4): 340-5.

|

Review Date:

12/20/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |